The mind-bending reality of climate disruption and what it means for our brains

Climate journalist Clay Aldern explains a frightening consequence of extreme weather events that we’re not talking about nearly enough

Pssst. Want to know one of the best things about working in the climate movement? Witnessing the explosive imagination of the people in the climate and mental health space. We’ve profiled a high school student who had a vision to shut down an abandoned gas well, and a university professor who thought to open a climate anxiety booth at her local farmers’ market. We’ve talked to people who can really and truly see a better way forward, despite immense opposition and setbacks from the status quo. If you want to help us imagine a big and bold future for Gen Dread, consider becoming a paid subscriber or if you prefer, support Gen Dread with a one-time donation through our partner, Small Change Fund. We’re so glad you’re here.

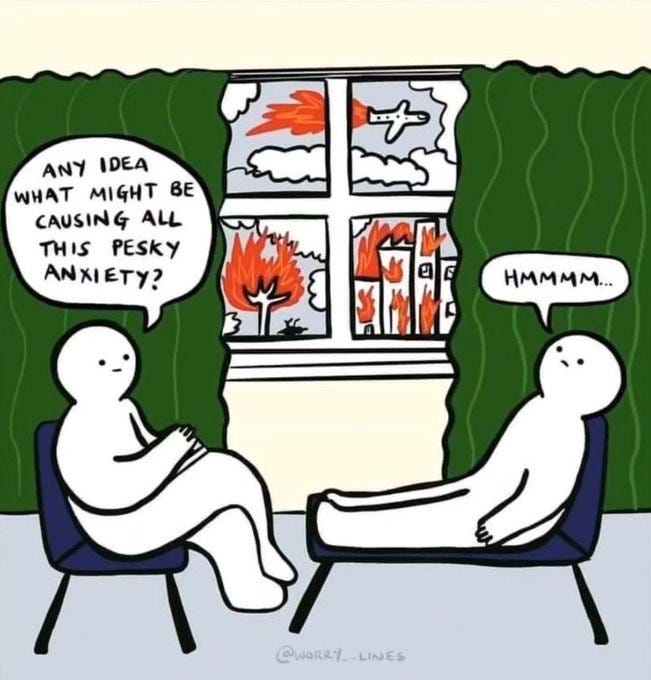

We know that extreme weather events can be brutal to cope with psychologically. But did you know they’re also really tough for your brain to deal with physiologically? In this alarming but crucial article from The Guardian, Clay Aldern explains how intense heat can impair a lot of our key brain functions: decision-making, critical thinking, emotional regulation, memory, and increased rates of neurodegenerative diseases. Clay is a neuroscientist and climate journalist who argues that a changing climate is not actually an external problem – it’s in fact messing with our internal cognitive machinery…and we need to start acknowledging this reality when assessing the magnitude of the crisis in front of us.

Clay explores these ideas in his new book The Weight of Nature, which is available now from Penguin Random House. We had the pleasure of talking to him about his findings, his reframing strategies, and his self-care.

That Guardian article is a good reminder that we’re not somehow separate from nature. Climate is not “that thing over there.”

That’s really the largest takeaway of this book: the fact that there is no separate self somehow walled off from nature, that we are indeed talking about a complex thermodynamic system that includes both the thing on the other side of the boundary – this nebulous “environment” and the thing within us, and understanding the porousness of that boundary and the relationship it implies between the self and the environment, I think are essential for something like climate action, in fact.

This stuff you're talking about – rising rates of ADHD, Alzheimer’s, and neurodegenerative disease – is alarming and hard for people to sit with. We've been fed this mythology that we are responsible for our health and we can do things to prevent or stave off certain diseases. But how can we cope with threats like these, which come with such a sense of powerlessness?

That's such a fundamental question here, not least because I think in addition to the gravity of some of these effects, it's also true that the nature of the effects in question is defined by a certain sapping of agency, right? If a changing climate is indeed forcing our hand with respect to aggression, decision making, various forms of critical thinking or executive function, this is a means by which the climate is reaching in, and indeed directly bearing on any kind of perceived free will that we might have. So I think there's kind of a double powerlessness there that we might feel if we really meditate on this stuff.

Where I tend to recover some sense of agency in this conversation and where I think it's useful to spend some time reflecting is in the fact that given the boundary that we were just talking about between self and nature is so porous, I think that we can reckon with a certain beauty of the intimate relationship we have with the world around us. The fact that we are enmeshed in a complex system that is twisting along through time and space and has been forever. And as the environment reaches in, we are reminded of that enmeshment. And I think it ought to suggest that we can also reach out, right? We don't need to be exclusively passive recipients of this weight. We can also push back. In practice, what does any of that look like? So many of the losses of executive function that result from something like a temperature deviation or increased heat are related to attention and impulsivity. And we have means for recapturing attention.

Mindfulness is a great example, right? Which I think is very frequently spoken about in slightly new-agey terms, but the contemporary neuroscience of mindfulness suggests that these types of practices, these types of mindful presences and modes of internal awareness and acceptance, the means by which we can notice the effects in question, and then notice other things that are going on in our minds and bodies next to those effects – appear to be, at a neurological level, intimately related to the restoration of the kinds of salience networks and attention networks that are suffering the greatest cognitive stress as a function of some of these environmental stressors. So at a purely neuro-physical and psychological level, it is possible to push back against the weights in question.

As a species, we’ve given the brain almighty status. It’s understandable why, but we’ve sometimes done that at the expense of inhabiting our bodies and a more holistic view of being alive. Is the information you're sharing perhaps an invitation to remember and reconnect with the rest of our bodies and the parts of us that are not rational, but more somatic and emotional and feeling…and is that maybe a good thing?

You’re right, the brain is not somehow separate from the rest of the body, and the mind is not somehow separate from the brain. The mind is rooted in the brain, the brain is rooted in the body, and in fact, if the brain didn't have access to both the body and the rest of the world, it wouldn't have anything to do. A brain in isolation is useless. The whole point of the organ is to model the state of the world and the state of your body and put together a statistical model that sets you, as someone with conscious access to this model, your expectations about what that world is going to look like and how you might interact with it.

I do completely agree that there's a certain deification of the brain in popular culture. And we would do very well to reorient our thinking about the organ in a manner that I think places it in the context of its home, which is our bodies. But this is not what we're taught. We are not taught that trauma is physical. We are not taught that any kind of neuropsychiatric condition is physical, but all of these things have a physical instantiation in the brain and the body, or else they wouldn't exist to us. We couldn't be conscious of them.

How did you feel writing this book? What came up for you on a human level?

I'm a climate journalist. So I'm squarely on the apocalypse beat. I'm used to the material I work on inculcating a certain sense of despair within me. And also because it's my job, I have traditionally been pretty good at saying, “okay, well, that's work.” And then when I shut my computer, I can have a life outside of work, in which I don't need to be obsessed with the end of the world.

But that line became more and more difficult to draw over the course of writing this book, in part because of the intimacy of some of the effects that I described and in part because it just became clearer and clearer that there is no shutting the computer, right? You can't unplug from the effects in question. There was a moment where I was reading an academic study describing increased county-level COVID-19 mortality rates as a function of exposure to point source emissions in counties for which during lockdown, EPA inspections had ceased and therefore point source emissions had increased. Because COVID is a respiratory disease, in the counties where the EPA inspections weren't occurring, you basically saw this causal relationship between increased emissions and COVID death rates. I was like, “man, that's so grim. That's so dark. Wow. What the heck??” I shut my computer to take a breath. And I looked out the window – this was the summer of 2021 – and it's just orange and black outside because there's a wildfire. And in that moment I felt true existential bleakness.

At the same time, I appreciate having access to the low points as well, insofar as it's important that we feel despair. It's important that we feel anguish in the face of doom. It would be inappropriate if I had looked out the window and been like, “yep, everything's normal out there!” So I'm actually glad that I’m compartmentalizing less now. That I am allowing myself to feel the weight of the problem at hand, because for me, reckoning with that weight is indeed the first step toward moving in the direction of any kind of action.

And what does it look like for you to sit with that weight and inhabit it fully? How do you make space for that?

I wish I could tell you that I have a fabulous meditative practice of mindfulness and I begin my days with an hour of forest bathing. I can paint an idealized picture of what I would like my relationship to these feelings and to nature – what I would like that relationship to look like. But in practice, I'm still a journalist who looks at a screen most of the day and you know, forlornly looks out the window. I do think that sitting with the emotions in question has inspired a certain kind of urgency in me and has inspired a certain kind of underlying purpose in how I think about my work. I think that I have moved from some semblance of journalism as a career that offers a paycheck mode of thinking to a certain kind of, “hey, I actually feel like I'm aligning my feelings and values with an avocation.” And that's everything. That's a really beautiful thing, to be able to consider the calling in what I'm doing, and for that thing to not necessarily feel like work. That's very profound.

Clay Aldern’s book The Weight of Nature is out now via Penguin Random House. Consider supporting your local independent bookstore when you pick up your copy!

If you liked reading this, feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack 🙏🏼

Making Waves

While climate anxiety is undoubtedly on the rise, we are also in the process of figuring out how to address it. Read more about what we can do to tango with it together in this article that Britt co-wrote for the World Economic Forum.

‘Till next time!

As someone living with chronic illnesses, I already notice huge changes in my symptoms depending on air pressure, pollutants, and weather events. I need to lie down on days where most people can function just fine in the heat. This Guardian article and this interview give me relief in knowing that other people are paying attention to this and talking about it. I feel less alone and less despairing in my own concern. Thank you so much for the work that you do.

Having backpacked in 115-degree heat in the desert, I can confirm it does affect your brain. It felt like I was functioning on lizard brain only, with the higher functions pretty impaired.