Welcome back to Gen Dread!

(For free weekly digests in your inbox about staying sane in the climate crisis, just hit the subscribe button below)

In 2004, The Guardian’s Science editor Tim Radford wrote “We're still waiting for the earth to start simmering, but by 2020 the bubbles will be appearing.” Kinda eerie to read it now, isn’t it?

Last year, with the extremity of the fires, the locusts, the superstorms (not to mention the pandemic), things really boiled over. Much life we loved got overcooked. These burns compel some of us to mourn the losses that have occurred, alongside future losses we know are only reasonable to anticipate.

This week, I bring you an essay on ecological grief and mourning from fellow Substack writer Adam Lerner. We recently discovered each other’s work and sensed clear resonance between what we’re both trying to do with our writing.

Lerner authors The Understory (a biweekly newsletter that “inspires leaders to act on the courage of their convictions in defense of the living planet and those who inhabit it.”) As a reader of Gen Dread, I think you’d like it. He wrote an incredibly thoughtful and well researched piece called Permission to Grieve, which weaves the ideas of grief experts together into a rich tapestry that provides some comfort. His essay also follows naturally from last week’s Gen Dread on Using grief, rage and dread to collectively wake up from the trance of denial. Make yourself a hot drink and get cozy, because it’s a long one.

I would love to hear whether this format — of making space for other similarly spirited writers from time to time on Gen Dread — is something you’d like to see more of. Let me know in the comments section, or if you’re reading via email, by hitting reply.

Oh, and I have some “eco-anxiety researcher/educator community announcements” to share! You’ll find them at the very bottom of the piece.

Permission to Grieve

The Understory: Issue Fourteen

By Adam Lerner

In his interview with Brené Brown, David Kessler tells the story of when Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was asked to join a program on national television after the release of her seminal book, On Death & Dying. The host opened the show:

“America, we have an important program about death and grief today. You may want to change your channel, but do not change it! You must listen to what we have to say. Elisabeth, look right in the camera and tell everyone why they should not change the channel.”

The camera then turned to Kübler-Ross who said, “If you want to change the channel, it’s okay. Maybe you are not ready. We’ll see you another time. Bye-bye.” I am going to follow the wisdom of Kübler-Ross to invite you to do the same if the timing is not right for you to invite grief in at this moment. But I hope you will stay.

When I started The Understory, I knew climate grief was one of the topics I most wanted and needed to cover. I know I am not alone in procrastinating grief. The topic is foreign to many of us, and most don’t have practices for how to invite, acknowledge, and feel grief. Because of this, we often delay the grieving process or obstruct it from entering our lives altogether.

I have started to invite grief into my life, but it has been a slow process. I laughed harder than I can recently recall in reading Jenny Offill’s novel of climate grief, Weather. I cried with Craig Foster as he fell in love with and mourned the loss of a cephalopod in My Octopus Teacher. I listened to Renee Lertzman discuss how climate change is an individual and collective traumatic experience. I bore witness to the grief of Jennifer Abbott in The Magnitude of All Things and to David Attenborough in A Life on Our Planet. I learned how to sit with grief and guide others with Climate Change Coaches and Becoming Ceremonial.

Grief has been an underlying theme of many of the works I’ve cited in The Understory. And, in a way, it now seems obvious. Of course grief is present for those espousing profound love of the natural world in the context of cataclysms to species and landscapes. I am starting to realize that grief is its own form of celebration.

Connecting with Reality

The first noble truth of the Buddha is that suffering exists. Think of this truth a bit like a gambit in chess. With the “opening move” that suffering is inherent in our lives, it creates a position for an inherent honesty in the Buddhist way of being. By starting with suffering, the Buddhist worldview embraces a holistic understanding of reality—one that is inclusive of pain as explained in Interbeing(1987).

In 1966, Thich Nhat Hanh founded the Order of Interbeing (Tiep Hien) in Saigon amidst the raging war enveloping Vietnam. Broken into parts, Tiep Hien could be understood as “tiep” meaning “being in touch with” and “hien” meaning “realizing” and “making it here and now.” Tiep Hien signified the importance of being in touch with reality of the world and the mind.

Being in touch with the mind is the inner life of feelings, perceptions, and mental formulations—“the wellspring of understanding and compassion” that can nurture us and those around us. The reality of the world is in the animal, vegetal, and mineral realms. To be in touch with the world, Thich Nhat Hahn invokes us to:

“Get out of our shell and look clearly and deeply at the wonders of life—the snowflakes, the moonlight, the beautiful flowers—and also the suffering—hunger, disease, torture, and oppression. Overflowing with understanding and compassion, we can appreciate the wonders of life, and at the same time, act with the firm resolve to alleviate the suffering.”

Buddhism teaches that it is only by embracing reality—“the unity of mind and world”—that we can be truly awake to the here and now. And it is in this conception of reality that I think we can learn a great deal about grief. Because what Buddhism tells us is that it is impossible to be in touch with ourselves and the world without feeling suffering.

If we are honest with ourselves, most of us don’t carry the full reality of the world because it is too painful to do so. And so, when it comes to the issue of climate change—where our land, water, skies, and species are suffering—we attempt to protect ourselves by turning away from the grief in our daily lives, redirecting attention to less painful things.

Those who maintain close living, working, and cultural relationships to the natural environment are confronted by the here and now of climate change. Nature writers, climate scientists, filmmakers, and Indigenous communities are on “the terrain of sorrow” and cannot escape the wider expanse of loss in our culture and ecosystems (Francis Weller, The Wild Edge of Sorrow, 2015). Their lives are interwoven with the natural species and places being destroyed, so they live the experience of loss daily. As shockingly described by Ash Sanders in “Under the Weather:” “they were not losing just their homes but their home, their sense of belonging to a place.”

But it is not only those people who maintain strong relationships with the land that have a painful view of our current climate changed reality. It is acute for environmental activists as well. Extinction Rebellion (XR) is noteworthy for their matter of fact embrace of reality, and for acknowledging the pain that comes with it. Waving the banner “TELL THE TRUTH,” XR is confronting those who willfully deny the reality of what is happening to our world.

XR is explicit in the significance of grief within the movement and provides support from grief circles to grief training to ensure that it is acknowledged and managed. In this training video “Tell the Truth,” XR Co-Founder Clare Farrell provides context for how rebels might confront their own grief and support others in theirs:

“Grief is a perfectly acceptable part of what we are doing with Extinction Rebellion...Grief is sort of a multi-layered affair. Some of you are quite young, so hopefully you don’t know as much about it as I do. It is important for us to make sure that we understand that when we talk about the reality of the situation that we are in as a species, it is quite difficult to deal with. And so, we ask people to be mindful of their journey through acceptance, and the realization of what it means. And also to be kind to one another. To find ways to be open and supportive to people, because different people have very different ways of dealing with grief.”

Acknowledging Grief

We tend to think of grief around the death of a person. But as David Kessler clarifies, grief is “the death of something,” not necessarily someone. Kessler further explains:

"We are all dealing with the collective loss of the world we knew...And we, like every other loss, didn’t know what we had until it was gone. And so here we are, and just like you, we’re all trying to find ways to virtually hold each other’s hands. We’re in this together. It is not going to be forever. It will end. There’s not a dark night that stays. And yet, we have to feel these feelings. We’ve gotta feel the grief."

Kessler frequently discusses grief as a collective journey. Sure, grief is experienced by individuals and therefore distinctive for each of us, but a changing world as we are now experiencing by COVID-19 and climate change is a loss shared by everyone. In that collective loss is the invitation to grieve, and to do so alongside many others. There is no map, nor a “typical” way to grieve. Kessler is careful to always mention that while there are five stages of grief outlined by Kübler-Ross and the sixth stage later added by him, grieving is not a linear process.

In “Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss,” co-authors Ashlee Cunsolo and Neville R. Ellis seek to better understand ecological grief and have drawn upon extensive research in Northern Canada and the Australian Wheatbelt. They differentiate between three types of ecological grief:

Grief associated with physical ecological losses

Grief associated with loss of environmental knowledge

Grief associated with anticipated future losses

We grieve for what we have lost, but also what we might lose. This helps to create a nuanced understanding of the myriad ways individuals and communities might feel grief. The field of study that emerged from understanding the psychological grief of climate change is called ecopsychology. Theodore Roszak is credited with creating the field and was critical of how scientific thinking deliberately excludes affective experience (see values laden science discussion in Issue 7). In The Making of a Counter Culture (1970), Roszak described the detrimental effects of splitting the internal and external worlds of scientists, whereby the individual experience is restricted to cold observation, while the external world is seen equally empty of affect. Francis Weller acknowledges an important distinction in an affectless nature: “we cannot grieve for something we feel is outside the circle of worth.”

Echoes of Roszak reappeared in October 2019 when three environmental scientists published a letter in the journal Science arguing it is “dangerously misguided” to assume scientists are dispassionate observers. The authors advocate for active strategies to help environmental scientists cope with their emotional distress—shockingly comparing the trauma of field biologists to those of professionals in the emergency medicine, disaster relief, law enforcement, and the military. Finding that many scientists experience “strong grief responses” to the ecological crisis, they discuss both the personal and environmental risk if their grief is not acknowledged, accepted, and worked through. “In doing so, we can use grief to strengthen our resolve and find ways to understand and protect ecosystems that still have a chance of survival in our rapidly changing world,” says co-author of the letter, Steve Simpson. Lead author of the letter, Tim Gordon said: "If we're serious about finding any sort of future for our natural ecosystems, we need to avoid getting trapped in cycles of grief. We need to allow ourselves to cry—and then see beyond our tears." (Science Daily)

image: “Extinction Rebellion Christchurch die-in, 27 April 2019” by Timothym (CC BY-SA 4.0)

What could be seen as countercultural to scientific objectivity are the processions being led around the world by the Extinction Rebellion. From “die-ins” where hundreds to thousands of people lay dead in public demonstrating mass extinction to funeral marches where protesters appear in black veils carrying coffins marked “our future.” While these demonstrations are marked as acts of rebellion, they should also be seen as acts of love. Love for one’s home. Love for other species. Love for the life-supporting systems of earth that are being diminished and thus creating a bleaker future for next generations.

Robin Wall Kimmerer beautifully summarizes how a deep relationship with the natural world is an interplay between grief and love:

"We can’t have an awareness of the beauty of the world without also a tremendous awareness of the wounds. That we see the old-growth forest and we also see the clear cut. We see the beautiful mountain and we see it torn open for mountaintop removal. So one of the things that I continue to learn about and need to learn more about is the transformation of love to grief to even stronger love and the interplay of love and grief that we feel for the world. And how to harness the power of those related impulses is something that I have had to learn."

Expressions of Grief

image: “Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970” by Retis (CC BY 2.0) | After 30 years of being underwater, Spiral Jetty reappeared in the Great Salt Lake due to drought.

In the Wild Edge of Sorrow, Francis Weller writes that most of us have forgotten the primary language of grief. If we cannot find the language to grieve within a societal context, we relegate grief to the shadows of our lives. And by doing so, we find it difficult to quantify and acknowledge the loss. Weller calls it our “sacred duty” to bring grief out of the shadow. The Bureau of Linguistic Reality is one such project. Rather than a dictionary of scientific terms, the founders have created a lexicon of neologisms that describe the destabilizing experience of living through mass climate change (Sanders).

Neimeyer and Cacciatore’s developmental model of grief (2016) suggests that we move through three phases: reacting, reconstructing, and reorienting. David Kessler reminds us that the process of grieving is not just about being present to our grief, but also having others bear witness to it. This is why the expression of grief is critical to healing from our wounds.

Perhaps Barry Lopez was thinking of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s quote, “what we cannot speak about, we pass over in silence,” when he wrote the following in his essay, “Natural Grief” (The Utne Reader, 1995):

“I find in the fabric of these woods—in their colors, convolutions, textures, movement, perfumes, their sonic amplitudes—a continuation of nearly everything I read. Among the vivid undelineated insects, in the image of a coyote moving smartly through stormlight after a rain or an osprey tearing a fish out of the river, looking at my own fistful of elderberries, I find an amplification of every kind of knowledge I've gained, from Bach to Vermeer to Stephen Hawking...I am silent in public venues for the most part...But my silence still rankles me...It is grief that makes me silent...Sensing the cougar and the bear are now cornered has compounded my grief...It is this deep, sprawling, diverse natural history, not objects (a bear, a fish, a bird, a tree) that is disappearing. And because my history is intertwined in this history, I can't purge the grief I feel unless I obliterate the affection in those memories."

For Lopez and other nature writers, grappling with their own grief of having intimately described landscapes, people, animals, and the inter-workings of our ecosystems only to watch them disappear in the span of their lifetimes is understandably heartbreaking. We should be grateful for Lopez and others who are now breaking their silence and expressing that grief publicly.

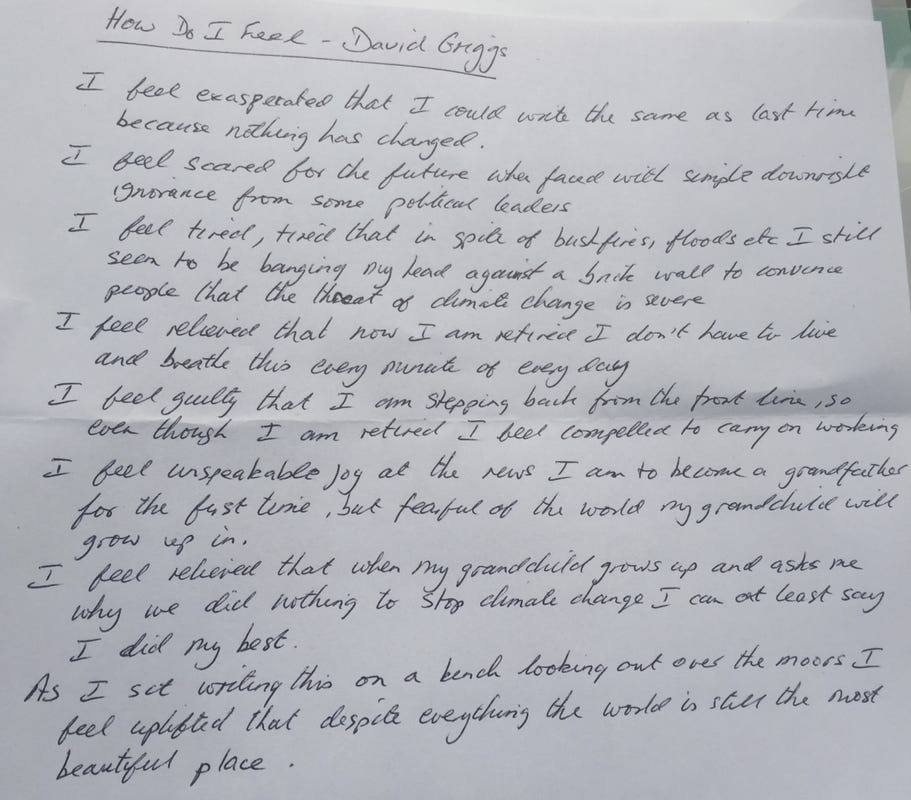

Starting in 2014, Joe Duggan approached climate scientists around the world with a single question, “How does climate change make you feel?” We are used to hearing objective, quantifiable data from many of these scientists. But Joe was interested in hearing something else. He wanted to uncover the emotional state of scientists who have spent years, sometimes decades creating, analyzing and presenting climate data. Under the project name ITHYF (Is This How You Feel?), Joe received over 40 handwritten letters that are posted on his website. They are a mix of anxiety, optimism, fear, hope, desperation, and surrender. I found this letter from Professor David Griggs of Monash University particularly gutting:

image: Letter from Professor David Griggs, Monash University (CC BY-ND 3.0)

In the Canadian North, Ashlee Cunsolo Willox together with five communities of Nunatsiavut, Labrador, authored a series of research papers and created a film sharing the voices and wisdom of the Labrador Inuit telling their stories of change, loss, and hope in the context of climate change in their environment. As part of their expression of grief and loss, in 2009 the “Inuit Nunaat” changed their name to “Inuit Nunangat”. “Inuit Nunaat” is a Greenlandic term that describes land but does not include water or ice. The term “Inuit Nunangat” is a Canadian Inuktitut term that includes land, water, and ice.

“As Canadian Inuit consider the land, water, and ice, of our homeland to be integral to our culture and our way of life it was felt that “Inuit Nunangat” is a more inclusive and appropriate term to use when describing our lands.”

To hear the voices and bear witness to the grief of the Nunatsuavut, I invite you to watch Lament for the Land and visit the project website.

The Other Side of Grief

Joanna Macy and Molly Brown describe pain as “the price of consciousness in a threatened and suffering world.” By inviting grief into our lives, we recognize its waxing and waning presence. Grieving is never complete, as our loss in the world never ends. Instead, we can embrace grief as a process of tenderizing our hearts and an affirmation of connecting with reality. Margaret Wheatley advocates not shirking from sadness, but rather “to let it in until our hearts are raw and open beyond recognition.”

In Real Change, Sharon Salzberg writes:

“We practice in order to cultivate a sense of agency, to understand that a range of responses is open to us. We practice to remember to breathe, to have the space in the midst of adversity to remember our values, what we really care about, and to find support in our inner strength and in one another.”

Salzberg calls this cycle a regenerative state. In her words, “The healing is in the return…Not in not getting lost in the beginning.” We need to experience the pain to find meaning. And in that greater meaning, we can find gratitude. The gratitude is not for the loss but rather the meaningful moments that come from grieving.

Psychologists Colin Parkes and Holly Prigerson write in Bereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult Life:

“In many respects, then, grief can be regarded as an illness. But it can also bring strength. Just as broken bones may end up stronger than unbroken ones, so the experience of grieving can strengthen and bring maturity to those who have previously been protected from misfortune. The pain of grief is just as much a part of life as the joy of love; it is, perhaps, the price we pay for love, the cost of commitment. To ignore this fact, or to pretend it is not so, is to put on emotional blinkers, which leave us unprepared for the losses that will inevitably occur in our lives and unprepared to help others to cope with the losses in theirs.”

As I reach the end of this essay, I now realize why it took me until Issue Fourteen to write about grief. I first needed to spend time expressing my love for the living planet and everything that is on it. From there I could connect with climate grief as an act of profound love, and permit myself to grieve for the loss of places that I once loved and for the future of a planet in peril. By giving myself the space to grieve and creating the practices that allow it into my life, I take comfort in having a community who I can grieve with. Unlike Aldo Leopold who said in 1949, “one of the penalties of an ecological education is to live alone in a world of wounds,” I am not living alone in a world of wounds. I have you. Thank you.

Conclusion

Many of us have reached a point where we can no longer ignore, suppress, or deny the painful loss of our natural world due to climate change. As Margaret Wheatley says, “we see clearly a world that others deny. The more clearly we see what is going on, the more heartbroken we become.” For those of us who are willing to accept the reality of the world and the mind, we are tenderizing our hearts for greater understanding and compassion in our lives. Yes, inviting grief is opening ourselves to pain. But we need not do this alone. When you grieve there are others there to support you. David Kessler runs a free Facebook group with daily gatherings for those who recently lost a loved one here. The Good Grief Network runs multiple grief circles weekly, which you can find in their newsletter. I am also fortunate to have some gifted professionals in my networks who can assist with different types of grieving. Please email me if I can connect you with any of them.

At the end of her essay in the book All We Can Save, Ash Sanders recounts a dialogue she had with a long-standing environmentalist. She asked him if he was sick. After deliberation, he answered, “I don’t know. But I know this: If your heart is breaking, you’re on my team.”

David Kessler describes a vision of hell where a man is brought into a dining room, hungry, and smells amazing food. The room is filled with people, each of whom has a spoon that is a few feet long, making it impossible to bring food to their own mouths. Then the man is taken to a different dining hall, this time in heaven, where they have the same spoons but everyone is feeding each other instead of trying to feed themselves. The difference between hell and heaven is taking care of each other. As Kessler says, “I’m going to witness yours, you’re going to witness mine. I’m going to feed you. You’re going to feed me.”

Be gentle on yourself and others. Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.

Adam

Community announcements

Are you working around issues of eco-distress, climate justice, or environmental education? The insightful women who brought you A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety (Dr. Sarah Jaquette Ray) and the podcast Facing It (Dr. Jennifer Atkinson) are creating an existential toolkit for climate justice educators, in book form, and they want your pitches and contributions. For more info, check out this link https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/GZZM93P . Deadline is March 1 2021.

Also, the Good Grief Network are offering a new round of their 10-step program for processing the uncertainty of the climate and wider ecological crisis. They’re a wonderful org. I’ve done the program myself and I definitely recommend signing up if you think you might need it.

Recent stuff from yours truly

Talkspace interviewed me for their feature Wellness in a World On Fire: Therapy Tackles Climate Change.

Michael Dowd interviewed me on his Post-Doom conversation series.

Get in touch

As always, you can reach me - and each other - by commenting on this article. You can also hit reply to this email or follow me on Twitter and Instagram.

Take good care of yourself and the ones around you. See you next week!

I am really honoured to have my writing shared with your subscribers, Britt. I think what you are doing with Gen Dread to bring attention to the emotional terrain of climate action is so vital, and love your approach that mixes scientific research with narrative storytelling. I am so pleased we found each other's work and connected. I am also looking forward to sharing your writing with subscribers of The Understory,

Upon re-reading this Issue, I had a huge sinking feeling in my stomach when reaching the passage quoting Barry Lopez. In fact, it almost brought me to tears. On December 25, Lopez passed away from prostate cancer. Within the span of just six weeks of writing Issue Fourteen, we lost one of our greatest nature writers. The story is heartbreaking not just because we lost Lopez to help us continue to navigate through the climate crisis, but also because after so many years of writing about climate change, Lopez passed away in a temporary home due to his home along the McKenzie River in Oregon having burned during the fall wildfires.

I take great comfort that he seems to have died just as he lived, gently, according to his wife and surrounded by family. She describes Lopez's final hours as the following:

"We played John Adams' music (a brother to Barry), we also played Arvo Part's "Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten" at full volume while we held him. In the final hours, we filled the room with Richard Nelson's (another brother) birdsong recordings—particularly the cackling ravens. We hung a self-portrait of Rick Bartow on the wall where Barry could see it. (Those two were probably already making mischief.) Barry's dearest Auntie, Lillian Pitt, guided us. The scent of herbs, the prayers, the fresh air through the windows. The light. We told him a thousand times, a thousand-thousand times, that we love him, that we will love him always, that he could cross his river now. At 7:21, he stepped in, with one last long breath. We washed him with water from the McKenzie River and wrapped him in a Pendleton blanket."

Orion Magazine collected reflections from many writers on the influence of Lopez's writing https://orionmagazine.org/article/writers-artists-on-the-influence-of-barry-lopez. If you are new to his work, I strongly recommend Horizon either in writing or as an audiobook.

Rest in peace, Barry. In grief, we love.