What's wrong with the term "climate anxiety"?

It runs the risk of medicalizing, depoliticizing, and dehistoricizing psychological distress

Hi and welcome back to Gen Dread!

Today we’re going to look at a term that I’m sure you’ve heard and may even use to describe what you feel: climate anxiety -- as well as its more encompassing cousin -- eco-anxiety.

I’ll be frank. I am very happy that we have these terms and that they’re finally getting used at an appropriate pace by more and more people. The need to describe the distress that so many people feel mirrors the reality of our existential ecological crisis. Climate anxiety and eco-anxiety are self-describing, though many point to the American Psychological Association’s 2017 definition of eco-anxiety as “the chronic fear of environmental doom” to make sense of it. These terms have helped transform the conversation around what the philosopher Glenn Albrecht calls “psychoterratic” syndromes into something acute, understandable, and active. They’ve also made it human. These are all good things. We need to talk about the subjective experience of living with environmentally-linked anxieties, and how they can be used to transform our collective responses to ecocide.

But these terms are not perfect, and in an effort to write the next headline or produce the next documentary, we often gloss over the ways they don’t help us come to terms with what we’re really dealing with.

What’s up doc? “Oh nothing, just a life-threatening planetary reality you should feel proud your body is responding to”

For starters, classifying any of these feelings as anxiety sounds like pathologizing. The mind churns in an attempt to compare it to other anxieties one might see a therapist for, like fear of flying, which statistics clearly show is based in catastrophic thinking and not real-world risk. But climate and eco-anxiety are completely rational to feel. You do not need to embellish any of the science to feel your chest tighten. The body’s stress response to our unfolding emergency is simply the body doing its job. It is trying to keep you safe and tell you that something is deeply and terribly wrong, which you ought to mobilize resources in the face of in order to make your situation safer.

Climate-aware psychotherapist Ro Randall reinforces this critique in her new climate psychology video series on Youtube. She says we should call it climate distress instead of climate anxiety, as anxiety allocates the feeling to a subset of humanity rather than all of us, and the feelings themselves are much more than anxiety (read: grief, shame, guilt, overwhelm, sorrow, fear, hopelessness, etc). I applaud Randall’s broadening it out, but personally I think distress sounds a little soft for what the feelings actually feel like. Do you have a suggestion for another term you think can do the job? Leave a comment below or get @brittwray on Twitter.

There are no universal categories of emotional distress

In this new thought-provoking paper in Clinical Psychology Forum, Barnwell and colleagues argue that “climate anxiety” cannot speak to the myriad social and environmental justice issues that shape psychological distress in the global south. Using South Africa as an example, where mines are often placed in majority Black communities, they describe how psychological distress is connected to underlying asymmetrical power relationships that climate change is now making worse. As one of their research participants described “The mine is violent, the government is violent, the system is violent. You don’t have peace of mind in the community [if] you are continuously in a fight for survival, which doesn’t come easy.” The impact of the climate threat on top of that kind of existing injustice cannot be understood unless it is explored within the specific history and politics of the mining community itself. Blanketing the emotions that climate change produces as climate anxiety in a place that has endured acts of environmental violence throughout time just doesn’t make any sense. It’s more like, “oh, quaint term global north, thanks for that!”

That said, we have plenty of ongoing cases of environmental injustice in the global north as well. The historical and sociopolitical contexts surrounding them no doubt compound the psychological distress that marginalized communities experience. For example, Ashlee Cunsolo’s prolific research in the circumpolar north of Canada demonstrates this. She’s documented the ecological grief that many Inuit people in Labrador feel as they witness the ice -- a vital part of their identity -- vanishing before their eyes, and how it is so much more than just grief. It is the emotional impact of experiencing colonization all over again, as their traditions melt away because of a crisis that they had nothing to do with creating. Meanwhile those most responsible for this crisis are employing the same industrial and extractive forces that colonizing powers first summoned the Inuit’s generational traumas through. So what Barnwell and colleagues are describing isn’t unique to the global south. But given the disproportionate amount of environmental injustice in the global south, hammering home why the term ‘climate anxiety’ is not sufficient through stories from the global south, certainly makes sense.

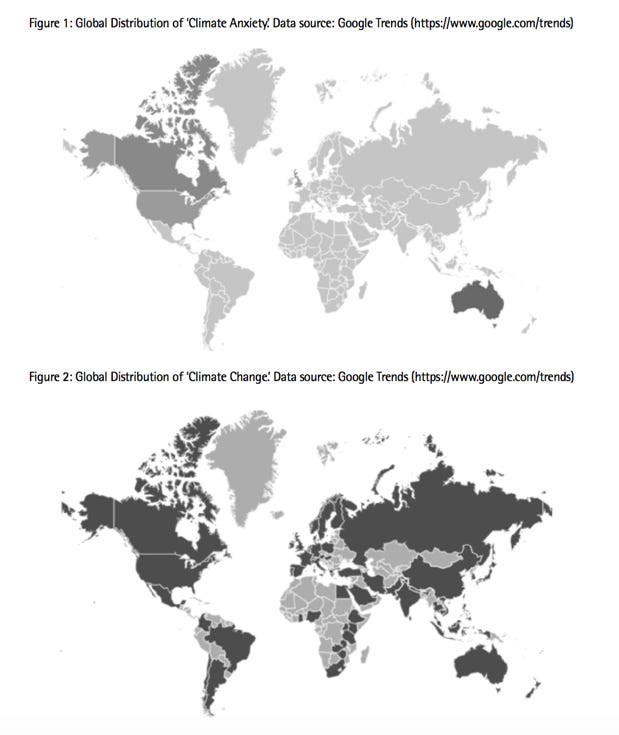

They ran an experiment to look at where the term climate anxiety is searched, and indeed, the only ones who seem to be typing it into their search bars are the Canadians, British, Americans and Australians. Part of this is of course due to language. The term is bound to not be popular outside of the English speaking world. But they also call into question the suitability of the term to describe people’s lived realities based on its striking absence in the global south - including the English speaking parts. In the maps below, the darker the country is, the more the term is searched there.

Power, Threat, Meaning

The researchers suggest that a better way of thinking about what the climate threat does to shape psychological distress on top of longstanding injustices is to apply the “Power, Threat, Meaning Framework”, or PTMF. PTMF is a way to discuss the social contexts of distress that psychiatric diagnosis typically obscures.

Here is a summary of how PTMF works from Johnson and Boyle (2018):

“this framework for the origins and maintenance of distress replaces the question at the heart of medicalisation, ‘What is wrong with you?’ with four others:

● ‘What has happened to you?’ (How has Power operated in your life?)

● ‘How did it affect you?’ (What kind of Threats does this pose?)

● ‘What sense did you make of it?’ (What is the Meaning of these situations and experiences to you?)

● ‘What did you have to do to survive?’ (What kinds of Threat Response are you using?)”

Useful eh?

Imagine if we applied each of those questions to every person we met and emotion we felt in the planetary health crisis. What kind of a more nuanced, compassionate, and just world might we be looking at?

That’s it for this week. Stay safe out there. Hug your loved ones. And consider, maybe some of us in the global north should make our Google searches a bit more like this:

Lastly, please help me get the word out about Gen Dread. We need more people to be a part of this conversation. Thank you!

Great to see the PTM Framework being used to address the issues of depoliticisation etc around 'climate anxiety'. I've been using it in my professional work with children with developmental trauma since it was released. Further looking at Indigenous understandings and framings of climate anxiety - with long roots in colonial exploitation - will help inform it better I think.

Thanks for sharing your insight on this, Britt! It brings a lot to the table and sheds a lot of light on how absurd it is that we reduce this existential feeling of dread down to "anxiety". This post inspired me to start up a local community space (well, virtual right now) to meet up with other young people to talk about the intersection of climate change and social justice. Keep up the great writing!