Why climate disasters call on us to take shared ownership of our own wellbeing

Social capital and connectedness are key when it comes to protecting mental health in the climate crisis

Hello and welcome back to Gen Dread, the weekend edition!

First off, news flash: on Monday October 5th I’m going to be co-hosting a webinar called “Making sense of climate anxiety - how we can cope when the future is so uncertain” and if you would like to join me, tickets are available here. I would be thrilled to meet you face to face, so hope to see you there! Feel free to share the event in your community.

Now if you’re up for some light history of sociology that underpins current psychiatric and epidemiological thinking around how we should tackle the mental health fallout of the climate crisis (because that sounds light, right?), grab a snack and read on.

Mental health grows from community health

These days, I often find myself thinking about this idea:

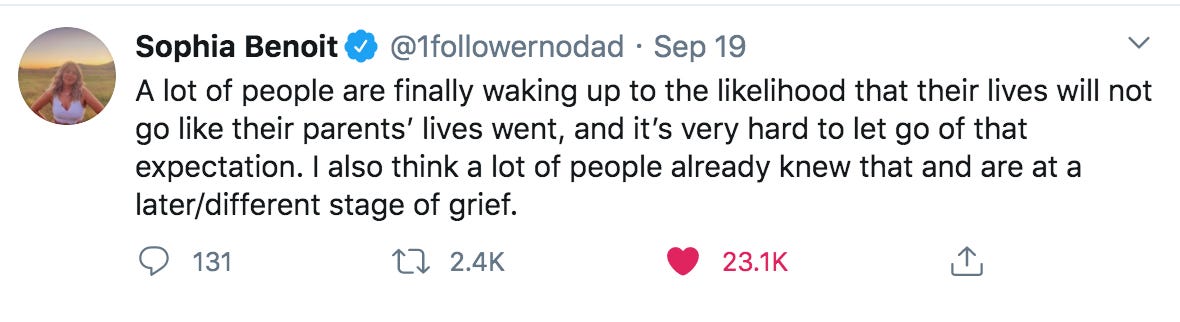

We are in a massive moment of collective awakening, though the pace of its spread is not equally distributed. Each time a new climate disaster hits, the adoption rate of eco-turmoil spikes, which sends newcomers into the fray of their own epiphany about how the world has dramatically and in some ways irreversibly changed. Naturally, as more people experience climate anxiety and ecological grief, the public discourse around these phenomena deepens. My google alerts for these terms are active as ever. What’s missing though, is a broad societal discussion about what needs to be done now to protect the mental health of people who are living in communities that are already being battered by climate disasters, and will likely experience more.

When we do have this conversation, it tends to focus on disaster relief and temporary counselling services that are sometimes offered to people who’ve just lost their homes to a wildfire or storm, or who perhaps never had a home in the first place. But we also need to go beyond those bandaids, to wrap our heads around the systemic changes we need to make if we are to defend the psychological wellbeing of frontline communities as climate disasters intensify. The most obvious collective solution is to reduce the direct climate threat with all we’ve got, though beyond that, there’s still a ton we can do to benefit. This is a topic I don’t dare try and cover in one edition of Gen Dread. Rather, consider this me jamming my foot in the door, and with time we’ll swing it wide open.

Psychiatric epidemiologist Helen Berry is the first person in the world to hold this badass title: Professor of Climate Change and Mental Health, which her former employer - the University of Sydney - gave her. Berry’s extensive research shows that if we want to improve the wellbeing of the most vulnerable communities as things heat up, we must shift the bulk of responsibility for mental health care from the biomedical model to the wider social environment. Specifically, this means helping communities increase their social connectedness and social capital (and future Gen Dread editions will do a more thorough job of explaining why this is). All you need to know for now is that Berry’s research demonstrates why we need a civic-minded approach to mental health innovation in the climate crisis; one that supports residents in a community to solve problems that they themselves define as being most concerning. Findings show that the entwined processes of self-determination, cultivating trust, and capacity building that are inherent to this approach, can prevent psychiatric harm in disastrous scenarios. Berry calls this “the pearl in the oyster” for mental health care in the climate crisis, and it was partly inspired by the pioneering work of a sociologist and psychiatrist named Alexander Leighton.

Image credit: Nova Scotia Archives

In the mid 20th century, Leighton began a several decades-long study of psychiatric problems in rural Nova Scotia, Canada. In the study, he followed a particularly disadvantaged community called The Road for more than 20 years. The 118 residents of The Road were poverty stricken, lived in shabby houses, spent their money as soon as they got it, didn’t plan for the future, hardly trusted each other, were socially isolated, had high levels of marital strife and child neglect, and showed serious mental health problems. Other people in the county thought that residents of The Road were inbred, delinquent, lazy, alcoholics who were not to be trusted.

In an attempt to help the community come together and not fall further apart, Leighton and his colleagues prompted local government officials to step in. They offered the residents help by prompting them to develop the kinds of social skills that foster cooperation. They also gave assistance in the form of education and employment opportunities. Things started to gel when the residents were encouraged to agree on a goal that they would like to attain as a group. They decided they wanted to raise enough money to be able to screen films in the local schoolroom, which didn’t have any electricity. As they were left on their own to figure out how to do this, they learned how to lead, follow, and cooperate. Eventually the cash was raised, the schoolroom was wired with electricity, and The Road got to enjoy their movies.

This successful pilot project was followed up by other goal-setting challenges until the community became so skilled at cooperating and solving their own problems that the entire quality of life there had shifted. By 1963, the houses were tidy, there was less drunkenness, the community was integrated into its surrounding region, and its residents avidly took part in church, school, and other community activities. Their confidence had improved, and so too had their attitudes towards the future and the state of their mental health. Leighton concluded that cooperating to achieve shared goals was the key to making this once impoverished community pull together and boost their own wellbeing.

Now imagine what this kind of approach could do for vulnerable communities who are living on the frontlines of the climate crisis. Instead of coordinating to get what’s required to watch movies, gentle institutional support could help the community come together to decide on whatever they wish to achieve. Maybe that would look like cultivating the conditions for local food security, dealing with toxic waste pollution, or getting residents equipped with low carbon air conditioners to prepare for the next heatwave. As more goals are accomplished, the community’s ability to solve its own problems would be trusted, hope for the future would grow, and emotional support would become widespread, translating into resilience. Then when disaster strikes, residents would be much more equipped to cooperate and rebuild.

Research has shown that this kind of community cohesiveness can even outweigh the effectiveness of economic assistance and relief from aid or government groups to improve wellbeing. And as Berry told me when I interviewed her for my forthcoming book, “at no point would the words mental health ever even need to be mentioned.” So in this sense, community building and activism are some of the most powerful tools for mental health care (but no, not cures that promise to fix it all). And of course, coming together like this can help anyone (not only the most vulnerable people) fight the myth of individualism, which is what caused this whole frigging mess in the first place.

That’s one more great reason to get to know your neighbours!

Why wait any longer to sign up for that community group you’ve been thinking of?

Unless, of course, you prefer the image on the right.

Follow the conversation

If you want to keep up with Gen Dread, follow me on Instagram, hit me up on Twitter, or reply to this email if you’re subscribed. And if you’re not yet:

More from me next week - have a great start to yours!