Are "eco" terms, like eco-grief, holding back progress?

Part 2 of my interview with environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht

Welcome back to Gen Dread!

If it’s your first time here, you can sign up for free emails about “staying sane in the climate crisis” by clicking the yellow button right there:

I hope you enjoyed part 1 of this interview series with environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht regarding “a new lexicon for a troubled planet”. Both part 1 and today’s part 2 are produced in collaboration with the multitalented brains behind Buckslip (do subscribe! As mentioned last week, if you want to get smart about media, culture, and “the humanities of global warming” among other things, I recommend you check them out).

Discussing Deep Adaptation

Before we get into part 2, I want to give space for a rebuttal to something that appeared in part 1. This paragraph in particular:

Albrecht: I'm into deep mitigation, which is, in a sense, the antidote to deep adaptation, which is now being expressed in various forms all over the earth. Ranging from mild forms of escapism to preppers who are buying New Zealand and filling their bunkers with what they think they need to survive in the ugly new world.

You may be familiar with the controversial paper Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy, which argues that near term societal collapse is inevitable due to the climate crisis. It often gets misconstrued as following its argument with the idea that we should therefore do nothing but get ready to sink beneath the waves. When actually, there is a community that has evolved around the paper, who gather on the Deep Adaptation Forum, and support each other in multi-directional ways. Many on there espouse civil disobedience and various kinds of “external” political actions that can help reduce harm, alongside grief-work and new forms of community building. That’s why it was included in Jo Hamilton’s research on “emotional methodologies” for helping people bear tough climate emotions and reflect on their capacity for action. Some people from the Deep Adaptation community (which I am not a part of) felt misrepresented by Albrecht’s description of there being a “prepper” or bunker-mentality caught up in their work.

Kim Hare, a dedicated member of the Deep Adaptation community, shared with me why she disagreed with Albrecht’s characterization. “For me, It’s all about enabling loving responses to our predicament, and building resilient communities. It’s much more about the inner work that’s necessary to stand tall and look at the reality of what’s happening – from a place of courage, compassion, love and wellbeing. After a period of profound grief… I found something unexpected on the other side. A deeper wellspring of peace, love, compassion, courage and wellbeing – and even joy. There’s massive growth in this.”

And Jem Bendell, the original paper’s author, offered this in response:

“Corporate and state media tell us that it is unhelpful or dangerous to accept our future is now one of decline and breakdown. Staff in such organizations, and the voices they promote, are demonizing those of us with that anticipation of decline and breakdown. What else could we expect from incumbents but initial fear of a mass awakening to the illegitimacy of modern economic and social systems? Despite that, people are connecting peer-to-peer to help each other find myriad ways of responding with compassion, courage and creativity. Philosophically and spiritually we are peaceful bunker busters not bunker builders. Many people with a mic on climate would do well to put the mic down, breath, grieve, and dialogue privately about what they think is unbearable to them. What comes after can be way more powerful.”

Albrecht then responded in turn with an apt critique considering the source. That is, one focused on language:

“One part of me says I am too kind to Deep Adaptation. The arrogance of the use of the word, "deep" for a start. It implies that all else is "shallow" or trivial. The philosophy of Deep Ecology (Arne Naess) went through that critique decades ago and I am surprised that it has been revived in this context. The term "adaptation" is also problematic. The meaning of that word is to 'fit' or modify in response to the changed circumstances or environment one finds oneself in. The emphasis in biology is, "Change or adjustment in structure or habits by which a species becomes better able to function in its environment, occurring through the course of evolution by means of natural selection."

So, the term "Deep" is simply rhetoric and the term "Adaptation" implies an adjustment to best survive in a changing environment which is inherently conservative in that the emphasis (responsibility) of change is on the organism (self) not on the environment (society). The more we adapt the more we fail to question the reasons for the change in 'the environment' that is forcing/requiring us to change. The more we focus on why the negative change is occurring, the more we can negate it.

That is why I have countered with Deep Mitigation. Of course, the term "deep" is there only to counter the equally facile use of "deep" in Deep Adaptation. However, to mitigate is to halt or prevent the cause of the negative change. That task I see as urgent!!!!! I would rather use the term 'Emergency Mitigation'.

According to the climate science I read, we (humans) still have a chance at preventing worst case scenarios for the fate of the planet under enhanced greenhouse conditions. That task I see as a vital part of entering the Symbiocene (not the only part). I think that all else is a distraction from this top level priority in human life.

If the climate science information changes to support the idea that we are in imminent danger of catastrophe ... sign me up for Deep Adaptation, as we will have no other choice. However, I would rather call that state 'Deep Extinction' (about six feet deep).”

Dear reader, I’m not trying to stir up some $*%t by hosting this debate here. However, I think it is an important one for us to be having, given the moment we find ourselves in and the varied responses people are taking. If you have thoughts about this exchange, please share them in the comments!

Okay, onwards to part 2 of my interview with Glenn Albrecht. If you haven’t yet, first make sure to read part 1, so this next bit will make as much sense as possible.

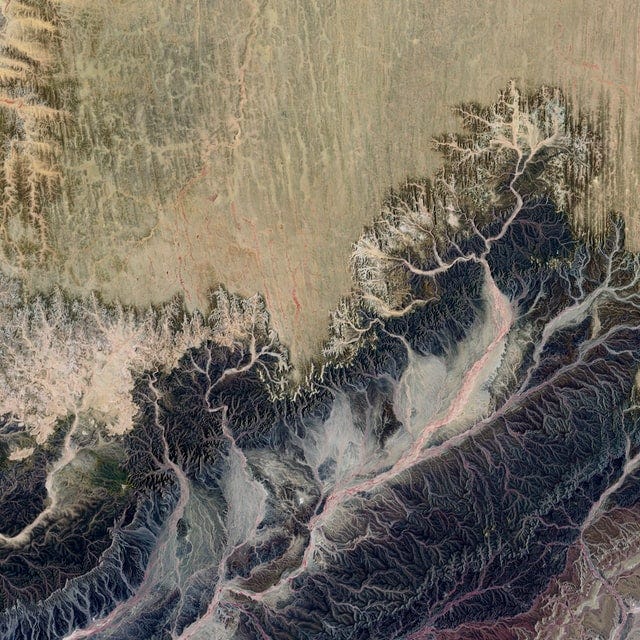

Photo by USGSon Unsplash

Part 2

BW: Clearly, you're a big believer in the power of words. How do you think we should be considering language in our quest to positively transform the future into something that is life sustaining? What is the role of terminology in this massive transformational moment that our species is in?

GA: Well, it's a complex question, and there are numerous avenues that I would try to address. One of them is the fact that the earth is now changing, and has been changed by humans to such an extent that the subtitle of the book remains relevant, which is "new words for a new world". So as a result, this new doesn't necessarily mean that it's good. It means that it's transformed in such a way that many of the past ways of thinking, the past language that we use to describe that older world, has either become redundant or it's been lost in the cultures and the languages of this world that have gone extinct. And the major point that I make in the book is that many of those older terms have now been appropriated or misappropriated by the forces of destruction. So, our older terms like sustainability, even the word "the environment" have become meaningless. I've listed a whole pile of words that have become an impediment to change rather than something that offers a pathway to transformation. Included in that is words like ecology, which I now see as becoming entirely meaningless. And in fact, is preventing us from seeing a future Symbiocene.

Why do you find the word ecology meaningless now?

The reason is because it's now being used with an eco in front of just about everything you can think of. Plus the word comes from the Greek oikos which is the root word for economics as well. Eco and economics have the same route. And the definition of oikos is the management of the household. So if you've got in mind that ecology is all about the management of our relationship to the rest of nature, then you're already on the path to industrial capitalism and putting dollar values on nature.

When we use the word, eco (hyphen) something, what does it actually refer to? Is there such a thing as an ecosystem? Of course, there isn't unless you put some content into it. It’s like a spray on solution for something that you don't have an objective or meaningful description of. I find that part of our conceptual problem is that we can't think beyond the eco any longer. And the world of business now uses ecosystem to describe virtually everything that it's doing. The same applies to the appropriation of sustainability.

The word resilience is now being used as a replacement for the concept of anthropogenic climate change under the old regime of Trump. I've written in some detail about perverse resilience, you know, things that are resilient but that should go away as quickly as possible. I've critiqued the concept of the environment, because it's obviously conceptually setting up humans as external to the rest of life in nature. That too is a kind of throwback to a time when we got our relationship to nature completely wrong. Another problem with eco in front of everything is that it does a disservice to Indigenous belief systems, it's a form of colonial thinking that replaces culturally imbued meanings with a system science one. That, again, is something that I find not a useful way of adding to the debate about our emotional and psychological relationship to the rest of life.

What are some of the forms of resilience you think we should do away with?

Well, at the moment, it's a technical term, which means we should bounce back to a formal way of existence. At the moment in Australia, for example, our government is talking about bouncing back to a previous state after COVID. And for them, that means that we should be reviving our fossil fuel industries, fracking more gas, exporting more coal. And that's all being presented to the Australian public as a form of resilience—that we need to return to a state that enabled us to achieve our great way of life. Well, the very thing that we ought not to be doing is being presented as resilient. So resilience is a dangerous concept and can be used to justify precisely the things that we should be avoiding or moving away from.

Is there anything else you want to add to that idea, just to give everyone a sense of what's preoccupying your heart and mind?

I'm very critical of the concept of grief being used in connection to ecology or climate change, because it devalues what's going on in humans, particularly during a pandemic of COVID-19. People are dying in the millions. But the climate, or ecosystems, whatever they might be, have not died at all. We haven't lost our relationship to them. It may be bruised, it may be damaged, or as Aldo Leopold called it, that we live in a world of wounds, but the wounds can be repaired and returned to health. And that's my task in life, it is to reject the idea that we are actually killing or murdering the sides of life. If I had reached that conclusion, I would be sitting in the corner rocking back and forth with my hands on my head. I reject entirely that response to the dilemma that we're in. So the writing of ‘meuacide’, the extinction of our emotions, is also going to involve a more substantial critique of grief and its applications.

Okay, that's very interesting. So you must then reject the idea that people can grieve their idea of a future that had ecological stability, which now is getting wiped away as they anticipate further climate change? There are a lot of people in the mental health and climate change space who speak of eco-grief as something that can be anticipatory. Where one expects unraveling and degradation of one’s community and traditions, because something in the landscape is disappearing that defines who you are as a people, for example. I'm just wondering if you reject grief in that context? And does that also mean that you're taking issue with people who say it's legitimate to grieve the future you thought would come that now you believe no longer will, in order to change your life appropriately?

It is just a misuse of the English language for a start because we have concepts like dread, which is precisely directed at a future that we don't wish to be in. Grief is something that most adequately describes a relationship that ceases to exist between people when somebody dies. It's the cessation of that which we would normally expect to continue to occur. That's what's so upsetting about death for most of us. It’s that this is a permanent cessation of that which was incredibly valuable in our life.

So when we see tens of thousands of people grieving because they can't be with their loved ones as they're in hospital beds, asphyxiating under COVID, or being buried in almost mass graves because of the sheer numbers, that's a really intense and extreme form of grief. If we're worried about the future, we have in the English language rich possibility and concepts to use, and grief is not one of them. Dread certainly is one. Anticipating the grief aspect of it is likely to distract us or prevent us from seeing what we need to do next. It's going down into that dark hole of prepperism and various other forms of maladaptive responses.

It’s not that I hate grief, I think I understand it reasonably well. I've experienced it in my own life. It's more that it’s useless. It's not providing us with something that Generation S can find useful.

Photo by USGSon Unsplash

Well, what about the intense emotions you might feel for the nonhuman world when you reckon with something like 3 billion animals that perished in Australia's Black Summer?

Well you can have a form of empathy for those creatures that died, but you didn't have a relationship with them. So far as I know, none of those species have gone extinct. So we can have a form of grief with respect to extinction when something is no longer present. But at the moment, there's only one species on the planet that's gone extinct because of climate change and that's a small mouse somewhere in the Torres Strait islands of Australia. Well, there is an element of grief in me about the loss of that species.

Trauma and other concepts that we have are relevant when it comes to the bushfires. Right where we live we had a massive bushfire, right on the borders of our property, so, I understand the fire issue. I just think that by throwing these old concepts around and pushing them together where they're not appropriate is not helpful. I don't say that because I'm just being difficult. I'm saying that we need a new language to describe the feelings that we have.

How on earth can the public understand what it is that we're talking about, if they don't even have a personal or deep psychological attachment to something like the term ecology? So then you even take away the cultural nuances of a cultural relationship to nature from Indigenous people. That's another huge loss. And then we expect people, that somehow they're going to emphasize or understand or even be able to respond to their own inner feelings, because we've put eco in front of grief? Well, I'm sorry, I'm just not impressed with that move. It's not adequate.

Solastalgia was created because we needed a term in the English language to describe a particular form of distress that's connected to the desolation of the environment. Well, that's what's going on, on a planetary scale right now. The new world that we started this conversation with is one that is being desolated. So we need more than solastalgia as a new way of describing what's going on.

What I'm saying is that we need to create a whole new lexicon in our language to describe these negative and positive feelings, emotions, states of mind that we have. And this is a really important task because by not doing this adequately, and just by being lazy, pushing together existing terms where people are comfortable within existing disciplines, is not actually very helpful.

I see your point. I'm wondering then how you think about the trade off between using language that the public is familiar with, has a grasp of, and knows how to mobilize in their own storytelling, and the hard work of introducing new unfamiliar terms that may sound academic, philosophical, perhaps highbrow and over the heads of the average person? Particularly since we're trying to collectively devise understandings around these concepts that are still relatively ignored and dismissed in society over all. What do we do about that trade off?

Well, I think we're really good at critiquing the fossil fuel industry and other forms of carbon intensive living and we now understand concepts like decarbonisation, or carbon neutral. I'm willing to do the same thing for our languages.

Also, I know, you've written about and interviewed people on the decolonial project. Well, the decolonial project is almost the same as the kind of project that I'm arguing for, with respect to our emotional engagement with the rest of life. If we discuss this whole situation in terms that are only comfortable for us within our past anthropocentric ways of thinking, then we're not going to make much emotional progress. Our emotional literacy is going to remain pretty well static or non existent.

I think it's better to be disruptive than it is to be ineffective.

So it is a difficult thing to get your head around. But I think it's better to be disruptive than it is to be ineffective. I'm keen to disrupt constructively, if there is a point to my being critical of the use of some of these terms. And I’m being critical of myself too because I've stuck eco in front of things in the past, in a way that now I cringe because I think, well I was just being lazy. I didn't really think about what was going on here. And it needs to be rethought. I'm not saying that I'm holier than thou, I'm just saying that this project, to be effective, has to be relentless and consistent. And it's like the decolonial project. There's virtually nothing that's untouched by it, including the psychoterratic. So it's a really important task and one that's relentless—a bit like trying to achieve the Symbiocene.

Some reflections

As a science storyteller who touches on the mainstream with my work (i.e. I’m not just academic in my aim), I’m not yet ready to let go of some of the more familiar terms like “eco-anxiety” and “eco-grief”, that I believe, help me to disseminate ideas about emotional distress due to a changing earth with wide-ranging audiences. Audiences that I can’t assume have much bandwidth for thinking about these concepts at depth. In other words, I’m still wary of the trade-off I asked Albrecht about, because of my exposure to how broadcast media and trade authorship works. But I am majorly admiring of the relentless nature of Albrecht’s decolonial lexicon project.

I am of the opinion that Albrecht’s methodology is vital for us now, and that we need to assist it. At this point in time, I do not take a binary approach. My forthcoming book is both filled with Albrechtian terms, and eco terms. For me, as an author and public speaker, I also do not feel that I can only write or speak in Albrechtian terms, because then I would be operating solely through the unique lens of another creator. There’s an inauthenticity and appropriation bound up in that. This then urges me to also create my own terms that can do the work better than the eco can, supporting Albrecht’s widening of the English language. That sounds worthwhile, and also daunting. Language creation is a deep and thoughtful process that requires serious labour. Just think of how long Albrecht himself has been refining these ideas! Solastalgia, his most famous term, is 17 years old.

At this moment, I don’t see how I can build time for adequate language creation into my already demanding workflow, and yes, after our discussion, I have to admit that perhaps that’s being lazy. That said, the provocation to be more specific and thoughtful about my language will stay with me even though I am comfortable taking the non-dualistic approach of using both kinds of languages discussed. No doubt, my discussion with Albrecht has challenged me on many fronts, and raised fascinating tensions that are entirely productive. Thanks so much Glenn!

Reach out anytime

As always, you can reach me - and each other - by commenting on this article. You can also hit reply to this email or follow me on Twitter and Instagram. I’m getting a lot of reader emails now, and I promise that I read each one, but it might be hard for me to adequately respond to every message. Thanks for understanding.

If you like, share Gen Dread with the people in your life who you think would appreciate it.

I’m having surgery next week, so I may or may not be able to get an email out. At the latest, you’ll hear from me in two weeks, and maybe sooner!

-Britt

So much to say and not enough time to say it all. It would require a full essay onto itself. So I'll briefly counter Albrecht's problematic coverage of grief.

First, grateful for Britt Wray's work and the reflection at the end of this piece. Grateful for the variety of voices included in GenDread. I extend my gratitude to Albrecht and his term solastalgia, because when I began researching what now fits under the umbrella terms of “eco-anxiety” and “climate grief” (a decade ago), he was one of the only ones talking about these complicated feelings.

Now, onto the critique: I'm frustrated by Albrecht’s discussion on grief, "I'm very critical of the concept of grief being used in connection to ecology or climate change, because it devalues what's going on in humans, particularly during a pandemic of COVID-19."

This argument seems to come from a scarcity mindset, like there isn't enough room for grief over the pandemic, so we can't afford to also grieve over the climate crisis. I assure you, we can (and must) grieve for human lives lost due to COVID and the impact that humankind (mostly industrialized nations) are having on the planet. We are complex enough beings we can hold grief for a multitude of things without it taking away from the grief over one issue.

GA: "climate, or ecosystems, whatever they might be, have not died at all"

The amazon is on the verge of becoming a savannah, icebergs are calving faster than we expect, sea creatures are dissolving because the oceans are too acidic, we're close to having more plastic than fish in the oceans, etc. To say our ecosystems have not died at all is a drastic misrepresentation of what's happening in the world. Do we wait until these systems and beings, are fully dead before we are granted permission to grieve them? That seems counterproductive.

I feel like he's telling me that I cannot grieve that my left arm has been crushed and no longer works the way it used to because it's still attached.

GA: "If I had reached that conclusion, I would be sitting in the corner rocking back and forth with my hands on my head."

Perhaps his insistence to keep grief at arm’s length is preventing him from sitting with the harsh realities of what we're doing to the planet, each other, and ourselves. It’s not just climate, it’s full out ecocide where we’re slicing up every habitable part of our planet and selling it off. It’s industrialized agriculture that commodifies lives. It’s the systemic othering and white patriarchy that allows us to mutilate and murder BIPOC folks and women. Climate chaos is a symptom of much larger systemic issues. I grieve for all of this.

With regard to restoring ecosystems: Yes, we can (and ought to) focus on regeneration and help ecosystems heal from some of the devastation humankind (again, largely industrialized nations) has perpetrated. Yet, we know from ecological succession that habitats never grow back the way they were before a disturbance. His insights shared here lack a biological understanding of how our natural world "heals" and what it means to engage in “healing.” Even if we stop all carbon emissions now (which is impractical and will cause significant suffering on a global scale), we cannot reform ice, stop micro-plastics from reaching every place on the planet (including the inside of our own bodies), or restore ecosystems to the level they were at before we devoured them.

Grief is a feeling of sadness over a loss. If we allowed ourselves to lean into it, to feel it, and come out on the other side, we are reminded that grief is what love looks like. We grieve because we feel that something is deeply wrong with the way humankind (once more, for the people in the back, mostly industrialized nations) operates on the planet. This is not dread. This is me feeling into the losses that I witness, that I feel in my bones, and that I choose not to turn away from. I feel grief because I know that I, as an individual, and we as a species, and culture, can do better.

There is deep wisdom to be found once you get to the humbling level of "rocking back and forth with (your) hands on (your) head." This sounds more like a fear of grief to me. An avoidance. We see this a lot in our Good Grief spaces. The dominant culture has convinced us that if we allow the despair or grief in, we’ll get stuck there. So, cultural messaging tells us it is our duty to remain committed to the positive, feel-good emotions (which are not in danger of going away and have been over-prioritized in the dominant culture). The invitation to lean into the heavy and painful feelings does not make us stuck there. As each of us acts with courage to actually feel and process the grief (a bonus if it’s in community!), we open to a whole new range of perspectives and energy that wasn’t available when we were avoiding or denying these feelings. We can use grief to inspire action, to motivate change, and to provide a depth of understanding about what it is we’re losing each and every day.

There is no shortage of positive emotions out there. But the dominant culture's rush to gloss over the heavy or painful ones stunt us and our emotional intelligence. It lessens our ability to collaborate and find new/nuanced solutions that are outside the systemic box.

Couple of thoughts. Thanks for the important discussion.

I did a book in Finnish (October 2019) about "ecological" feelings & emotions: feelings which are significantly connected with environmental issues. There’s always many factors at play. Sometimes the ecological condition and relation is the exact cause of the emotional reaction, and sometimes the reaction is the results of multiple factors.

In the book, there’s more than 100 feeling words. In relation to grief/sadness, I ended up using 8 main words and then discussed several sub-forms of them. Sadly (sic), the book is so far available only in Finnish, but a couple of the ideas are in my essay for BBC Climate Emotions series (link at the end of the post).

My main point with the above is that there are numerous kinds of ecological grief/sadness. I have personally seen in my work as workshop leader (and as a participant) the potential empowering effects that encountering grief&sadness can have (echoing Laura S. above). It is sometimes helpful to name particular types of ecological grief&sadness, such as “climate-childlessness-grief” (see Amanda’s comment above, I have a Finnish name for this feeling in my book), or “climate-bittersweetness” (when the ‘weather’ conditions allow you to be happy, but in the background is the sadness about the vast changes that are going on).

The second point is that, in my experience and based on research, ecological emotions & climate feelings (whatever terms we use of them) experienced at any given moment are usually combinations of several feeling tones. Some of these combinations are more common, such as sadness + guilt, or dread + grief (see Leora’s comment above), but then there is a huge number of various conglomerates. For example, sadness + flares of indignation + anxiety about freedom & responsibility + strong desire to do good (aspiration, in Renee Lertzman’s terms). Thus, in addition to the important task of discussing and recognizing various emotions & feelings, there’s a need to encounter the mixes, the assemblages, the conglomerates.

I think that in addition to more nuanced discussions shaped partly by academic studies, we should encourage people (and each other) to explore feeling words. And we should respect the ways in which people like to describe their emotions: if the words speak to them, if they help them to make some sense of what they are feeling, the words are valuable. That’s a key reason behind solastalgia’s popularity, and behind the growing popularity of ecological grief, I think. With these words and the explanations of them that others have offered, people have found insight about what they already were feeling – and growing understanding of what others are feeling. That way this whole enterprise has a strong ethical dimension.

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200402-climate-grief-mourning-loss-due-to-climate-change?utm_campaign=Hot+News&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=85704446&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-_jmsb10miJso8-STDmVaSO5qsPmiY_8kpnyT4G7jpvJQL7zedMIhPU16RHY19OOzO5eVcz51aVHjTBNyksZeEDsML5bQ&_hsmi=85704446