The oft-overlooked psychological wounds of climate apartheid and climate colonialism

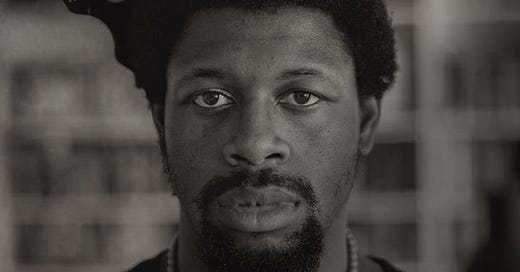

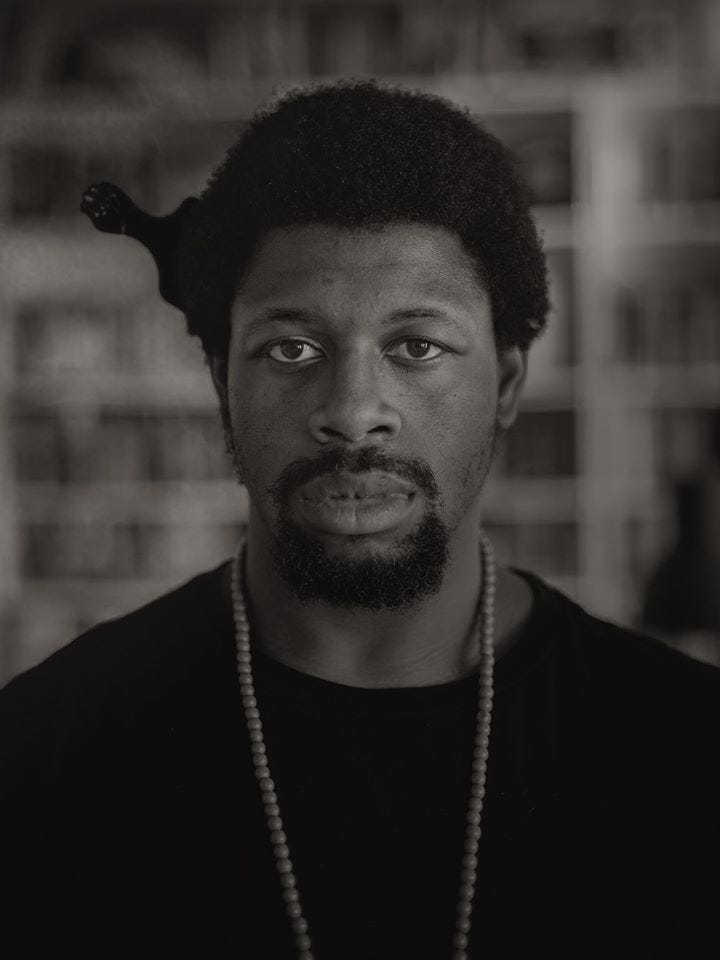

An interview with philosopher Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò

Hey Gen Dread head!

I regularly find myself thinking about a quote from the humanitarian designer Vinay Gupta that I came across several years ago while researching for my forthcoming book. It’s a statement directed at privileged people in countries like the US and UK who are concerned about climate-caused societal collapse. Being one of those people, it sure put a lot in perspective for me.

That quote is:

“Collapse just means living in the same conditions as the people who grow your coffee.”

This week, I want to explore two hugely important concepts that hold connections with that quote: climate apartheid and climate colonialism. I also want to dig into the psychological wounds they cause, which aren’t often talked about. In order to do this, I reached out to Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University. Táíwò is currently working on a book called Reconsidering Reparations, which explores the connection between reparations and environmental justice. In his public scholarship, he’s driving forth a conversation about the case for climate reparations. That’s the idea of getting high emitting (especially Western) states to grapple with the role they’ve played in creating climate chaos, and making them pay for damages to the countries where they’re owed.

Before we get into it —- if someone sent this to you, you can sign up for free weekly emails about ‘staying sane in the climate crisis’ by hitting the ‘subscribe now’ button!

What is climate apartheid? What is climate colonialism?

According to Táíwò, climate apartheid and climate colonialism are essentially the same concept, just at different scales. Climate apartheid describes the reorganization of a community or a country into a social hierarchy defined around who can protect themselves from the worst effects of climate crisis (either by paying for that protection or mobilizing other social resources). This results in a sharp divide: people at the bottom, who are left radically insecure, and people at the top, who make themselves relatively secure. Increasingly, Táíwò says, this is what hierarchies - whether they’re class hierarchies, racial hierarchies, or other kinds -- will be centrally organized around.

Climate colonialism just repeats this trend but more expansively -- across entire countries or regions of the world. Táíwò foresees that it will likely become the central axis of power in the world as the climate crisis accelerates. “Who can take resources for land, water, and energy production in order to protect themselves from the worst ravages of climate crisis and who can't -- that's increasingly going to determine geopolitical hierarchies just as surely as it determines hierarchies within communities and hierarchies within nations” he said.

I learned a lot from our discussion about how we ought to think about these growing drivers of inequality when we’re trying to understand them through emotional and psychological lenses. I’ve included our full conversation below, and I know this week’s post is long, but I promise, it’s worth it!

Photo of Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò by Jared Rodríguez http://www.jaredrodriguez.com/

BW: The mental health fallout and psychiatric trauma from climate disasters is well understood, and is known to disproportionately affect people in the Global South. There’s rich data tracking the PTSD, suicidality, depression, and so on that can set in after a hurricane or drought, for example. What I’d like to talk about with you today goes beyond these acute trauma impacts of disaster, and into the realm of ambient emotional distress — feelings of despair, hopelessness, sadness, grief, worry, anxiety, whatever it might be — in the face of a general awareness of the climate crisis, in countries where we can say that climate reparations are owed.

I write a weekly newsletter about “staying sane in the climate crisis” and I sometimes get readers emailing me from low and middle income countries telling me that the conversation about emotional distress that is rising in the West about the climate crisis does not map onto where they’re living. This is because people there are often struggling just to get through their day and survive. In other words, they’re already living the hardship that the privileged fear. That makes sense.

At the same time, the hardship they’re already experiencing is caused by the same unjust structures - imperialism, colonialism, and so on - that will disproportionately harm them in the climate crisis going forward. I’m then left wondering, doesn’t this need to be responded to on an emotional and psychological level? Instead of just talking about the fisheries that are drying up and the houses that are blowing away in storms, what about the psychological wellbeing of the most vulnerable communities in these countries? Given this, I'm wondering what your thoughts are about what it means to consider the emotional and psychological wounds that the climate crisis inflicts on the most vulnerable people who are living in the least resilient countries.

OT: I'm of two minds about this sort of thing. On the one hand, this is an interesting and underappreciated aspect of poverty and oppression itself. So the kinds of conversations that we are comfortable having around other sorts of gaps, like the wealth gap for instance, or the differences in doctor to patient ratios in developed countries versus lower income countries, I think, as you're getting at, there is an important kind of under-addressed gap. One, in what you might think of as mental health services. But I think by broadening out, the bigger story to tell about the disproportionate experience of trauma and stressors of psychological and socio-varieties, is exactly as you said, one of the underappreciated domains of results from colonialism and imperialism and wealth inequalities. The fact that there is more violence in one part of the world, for example, doesn't just mean that the death rate is higher; it means this characterizes people's experience in a much broader sense than that. So I think this is an aspect of the fight for global justice that works really strongly by way of the argument that you're mobilizing. If we look at the full ramifications of having a world that has these systems of oppression, that's going to include poverty and worse physiological health rates, but it is also going to include worse mental health rates.

On the other hand, because that's true, a public health perspective on mental health has decisively shown that these social determinants of health -- how income is distributed, how hurricanes are distributed, those sorts of things -- are important in part because the kind of stress they cause has both physiological and psychological ramifications. Part of what is important about addressing the climate crisis so that the hurricanes aren't so bad, part of what is important about making adaptive and resilient infrastructure, is precisely what you're talking about. Not just whether people have clean water or not, but how traumatized people will be from all these sorts of things.

BW: Has post-colonial and anti-colonial thought tried to account for the psychological and emotional wounds of colonialism, and might this be something that can be pulled into conversations around climate colonialism and therefore climate reparations?

OT: Yeah I think so, and I think there has been a lot of focus on direct relationships of the acts of violence and subordination that came with colonial domination, and trauma downstream of that --- whether it was from authoritarian social structures or the reification of existing hierarchical structures. But I think the broader story to tell includes things like wealth inequality in itself, and the psychological effects of that. Or infrastructural development or lack thereof, as is characteristic of much of the African continent, and the psychological ramifications of that, as well as the resulting food insecurity, housing insecurity, and insecurity from interpersonal violence. Once those stories are told, I think there will be very tight connections between reparations, climate colonialism, and this kind of broader psychological story.

BW: Do you then think it is fair to say that if we are going to build the more just world that we all want to live in, that we need to get granular about what the emotional and psychological impacts of the climate crisis are on people? As opposed to talking about its disproportionate impacts on communities in only scientific, infrastructural, technological, and political language, as is typically done?

OT: I think that is true but I think it matters deeply how we get granular about these kinds of psychological and emotional stories. My opinion is that we should be careful about a couple of things. One is whose emotions we are keeping track of and analyzing at a granular level, which is an issue that is raised in this article. And circling back to the point you made earlier, where people in the Global South are like, well, there's a way of talking about climate anxiety and climate grief that kind of generalizes from a not particularly globally representative class position. Therefore a granular analysis of the kind that you're thinking would have to make room for what you pointed out, which is that for a lot of people, in a primary and direct sense, there isn't a complicated emotional story to tell, or even an emotional story to tell at all with the climate crisis. What people have an emotional reaction to of course is the wildfires or the locust swarms or the pandemic or the flooding, and so an emotional story that looks at climate crisis in that kind of capacious sense, and not from a Global North-centric perspective, I think is a powerful way to think about it.

Because at the end of the day, we're not trying to stop hurricanes, we're not even trying to stop low crop yields. We're trying to stop suffering.

And if suffering never enters the picture of what we're talking about, it is hard to see how we are going to get things right. It would be as if it were an accident if we preserve a possibility for happiness for many of the people on this planet. The mistake that is being made is that people are having this conversation about adaptation and mitigation as if they don't have anything to do with these other conversations about how people are feeling, and whether people are traumatized, and so forth. These have to be integrated conversations.

"Sepak Takraw from Schagen's World Map (1689)" by oschene is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

BW: Do you have any thoughts about the character and nature of the psychological and emotional wounds that climate apartheid and climate colonialism cause for oppressed communities? And are they recognized in the discussions around climate reparations?

OT: One of the benefits of appealing to these well talked about concepts, like apartheid and colonialism, is that I think the story about how people emotionally metabolize it is probably pretty similar across these cases. What is different is the causal story --- like, why is it that poverty means you are rendered especially vulnerable to houselessness from natural disaster? Well it's because we've organized society in such a way that only certain people enjoy security from natural disasters and from the arbitrary will of police and so on and so forth. So on one level we have stuff to draw on already in terms of questions like, how do people feel about being hyper policed in Nairobi or in São Paulo or in Port-au-Prince? But obviously it won't just be the why that changes as climate crisis and climate apartheid and climate colonialism accelerate, it will also be the what.

So, being hyper vulnerable to policing is obviously bad enough, but being hyper vulnerable to police violence and flooding is maybe a compound level of trauma. And as these compounding environmental and sociological traumas take up more and more of our social ecology, we're going to face, probably, much deeper levels of social trauma, much higher levels of maladaptive behaviours, much higher levels of conflict than much of us are used to.

BW: How do you see the role of emotions in climate reparations work?

I think that, one, activists and organizations working for climate justice are going to look a lot more like the restorative and transformative justice movements that are working towards police abolition than your kind of “tree hugger” stereotype that environmental movements have inherited from past generations. And I think the reason for that is very much the picture you're working with. We cannot understand the crisis at the level of what matters just by looking at the science of what the wind and rain is doing. At the level of what matters, we can't understand the crisis other than the risk of total or partial sociological rupture. And when we understand it that way, and we understand the role that emotions and our individual and community-level ability to process those especially strong emotions that have to do with trauma has to play, it is going to be part and parcel of what we have to do.

It is not just a similarity of goals between transformative justice, organizers who are working to end racist policing, and the climate justice movement. It is actually that they have the same goals.

In both cases, what's happening at the bottom is we're trying to move away from a punitive, egalitarian model of how security is produced and for whom security is produced -- one that leaves a lot of trauma in its wake for those who are rendered prey to the system -- and trying to move to a much healthier model where we protect each other from harm even when some people are responsible for that harm. At the level of how society is organized, I think that demands the same kind of changes, whether what we're thinking about primarily is the climate, or what we are thinking about primarily is the police.

BW: Climate apartheid and climate colonialism are a hell of a lot to see here now and increasingly coming. How do you cope, just as a human, as an individual, with all of this knowledge given that you're paying attention to it all the time in your work?

OT: Yeah, you know, it's horrifying. The situation is dire and there are some positive developments but there are also a lot of negative developments. For me as a person there are two things that keep me going and that prevent the worst versions of despair.

One of those things is the psychology of collective action and just the psychology of action itself. Part of self defence is just figuring out how to actually defend yourself, making it more likely that you'll be able to defend yourself from a certain kind of harm, whether you're an outdoorsy person learning to survive in the wilderness, whether you're learning to fight, whatever it is. But part of it is ending the relationship where you relate to that harm as a kind of passive actor that history is just going to happen to, and building a version of yourself where you're playing a part in what happens. And with that shift comes a difference in your perspective, psychologically. Whether you are going to win or not, I think you just relate to disaster in a different way if you're thinking of yourself as someone who is going to act, who has a role to play in deciding how things go. It staves off certain feelings of hopelessness, certain kinds of fatalism, and it makes you invested in the practical possibility of things going well or at least better than they could. So that's important to me. It's not about thinking that things are going well, but it is about thinking that I'm not helpless, and that's important.

The second thing is the political perspective that I come from. I do political philosophy out of a particular set of intellectual traditions, which includes the Black radical tradition and the anti-colonial tradition, especially African anti-colonial thought. And for much of the last five centuries, things have been much worse for us. Yes, tomorrow looks dire, but my ancestors dealt with the transatlantic slave trade and Jim Crow and colonial apartheid. And while what's happening today is neo-colonial and is not in any way just, it is in fact not as bad as things have been for us. And so there is a kind of sky is falling mentality that is precluded from that political perspective.

BW: That makes a lot of sense. Thank you so much for taking the time for this conversation!

Other updates

I’m on the latest episode of The Brand is Female podcast, where host Eva Hartling and I discuss “the intersection of feminism and climate issues, how the pandemic has effectively reprogrammed the DNA of our global consciousness, and how racial and health inequities have been amplified by the pandemic; revealing how broken our system truly is.”

Get in touch

As always, you can reach me - and each other - by commenting on this article to let us know your thoughts. You can also hit reply to this email or follow me on Twitter and Instagram.

If you like, share Gen Dread with the people in your life who you think would appreciate it.

Thanks and see you next week!

Hugs,

Britt

Thanks Britt!

I think this point is super important:

"But part of it is ending the relationship where you relate to that harm as a kind of passive actor that history is just going to happen to, and building a version of yourself where you're playing a part in what happens. And with that shift comes a difference in your perspective, psychologically. Whether you are going to win or not, I think you just relate to disaster in a different way if you're thinking of yourself as someone who is going to act, who has a role to play in deciding how things go. It staves off certain feelings of hopelessness, certain kinds of fatalism, and it makes you invested in the practical possibility of things going well or at least better than they could. So that's important to me. It's not about thinking that things are going well, but it is about thinking that I'm not helpless, and that's important."

And it makes me wonder what percent of people have which mindset today - helpless/passive vs. active/has a role to play in deciding how things go.