Post-traumatic growth after touching death

A conversation with climate activist Charlie Hertzog Young

Hi there!

Welcome to Gen Dread, a newsletter about how the climate crisis is making us feel, why that’s happening, and what we can do about it. Subscribe now to find community, comfort, and practical coping strategies from experts all around the world.

**TRIGGER WARNING: The conversation below involves details and discussion of a suicide attempt. Please take care in whatever way is most helpful to you. A list of resources and crisis hotlines is available at the end of this article**

This is a difficult story to hear

For some people, climate distress is life-threatening, life-changing, and then, eventually, life-giving.

In 2019, climate activist Charlie Hertzog Young jumped off a six-storey building. He’d been consumed by oppressive anxiety, depression, and despair about where the planet was headed. He’d been suffering from pre-existing mental health challenges that had him hallucinating a wolf-like creature that followed him everywhere and attacked him without warning. He watched helplessly as the 2009 UN climate talks in Copenhagen dissolved into yet another stretch of apathy and inaction. Then a decade later, the only option he saw was to jump.

Charlie spent a month in a coma. Doctors had to amputate both of his legs. He woke up, newly wheelchair-bound, just as the world was heading into its first COVID lockdown. His recovery has been long and slow, a period that’s forced him to reckon with how a human being keeps going – and why – after he’s tangled with such intolerable depths of despair.

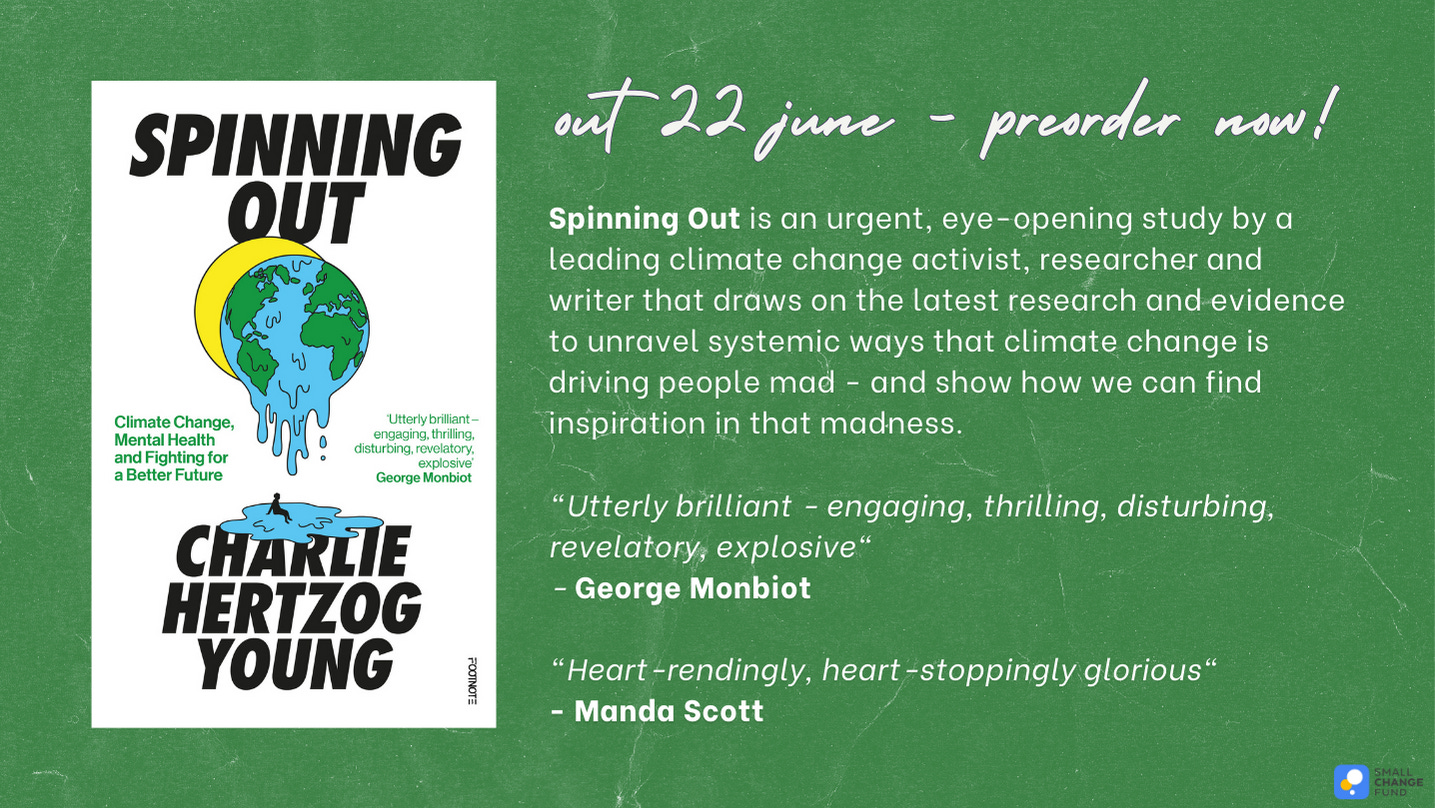

Charlie has emerged with some powerful realizations about the way climate chaos feeds mental health problems and why our culture isn’t set up to adequately support people in real distress – all things he writes so eloquently about in his new book, “Spinning Out”.

Here is Britt’s conversation with Charlie Hertzog-Young.

BW: When someone’s climate despair strips the world of meaning for them, and they’re in the darkest place imaginable, what do you think they need most at that moment?

It took me a decade of depression, anxiety and suicidality to start understanding this myself, but what allowed me to start healing was sanctuary, support and direction. For a long time I was kept safe but only really had access to very individualized treatments, whether that was medication, one-to-one therapy or ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). It was extremely isolating, and it wasn’t very healing, but I was kept from harm. What fundamentally changed things for me – and I need to caveat that this is just my experience (although I’ve heard it echoed by many, many others since) – was being given the breathing room to actually process what was happening to me, then being introduced to modes of recovery that let me move through my challenges and come out changed.

A lot of our conventional responses to mental health issues are fundamentally about fixing something that’s broken in our heads, rather than respecting the lived reality of the person suffering. People in states of deep distress need sanctuary. We need to be heard, not combatted or fixed. We need to feel safe, then to patiently ask – what next? What supports do we want and need to be able to grow from this? Depending on the person, do you need help with structure, with getting into the habit of showering and washing your clothes, are there substance issues, could you benefit from a peer-to-peer support group, is there capacity for you to take time off work (is there a hardship fund you could access?), who can support you with that? Eventually: what would you like your life to feel like? It can be thought of as offering space, light and a trellis to an ailing plant, the protected but connected environment to guide and support its growth, never forgetting the other plants around it giving it nutrients, shade and care.

You can’t rush these things. If you do, it’s very easy to rush back into the world when you think everything’s “normal”. The two most valuable things I got from being in psychiatric units were enforced safety in times of extreme danger and the relationships I built with other patients. That said, it wasn’t until after I jumped off a six-storey building that I found world-shifting therapies like whole person recovery, generative somatics, recovery coaching and community-based healing. Before that, I was repeatedly rushing to fix myself, then rushing back into the system that had made me sick. It was a compulsive cycle that very nearly killed me.

The support climate activists ACTUALLY need

BW: You write about how common it is for activists to have mental health issues “because of the way they are treated by society.” I of course agree. As activists, the experience of marching an endless uphill battle against the oppressive downward stride of harmful and entrenched systems is bad for personal wellbeing, especially when that process is not intentionally supported with self-care skills, nourishing community, ancestor work, therapy, take your pick.

If you had to narrow it down, what single form of support would you wish in your wildest dreams to become available for all climate activists (even in all their diversity) if you could snap your fingers and make it so, right now? And why? What transformative effect might that have?

I really appreciate the question, it’s very important.

I’d say focus on joining, building and learning from within communities of care. Communities of care come in many forms, at many scales, from our own intimate personal relationships to our neighbourhoods, and formal and informal medical supports, organizations, unions, mutual aid networks, cities and ecologies. I think what distinguishes these spaces from conventional ones is that they’re based on reciprocity, shared support and a prioritization of relationships over specific goals. There’s also a surreptitious joy. They let us step outside of the dominant culture in a radical way. We prioritize reconnecting with each other on an equitable footing, which is a massive departure from the status competition, unnecessary (and unhelpful) urgency culture and the dominating behaviour that exists in our jobs and our forced positions in relation to political power. This ideology sneaks its way into activism, too.

As activists – however we define the word – we need to feel safe. We need agency. We need to be part of loving spaces. This, counterintuitively, can make us more pragmatic, which is a big deal if we’re going to build a different world. These spaces are proliferating. A lot of the most exciting and effective activism today is done by people who wouldn’t necessarily identify as activists – an important point made powerfully to me by Ewa Jasiewicz from the National Movement Lead for Healing Justice London. These kinds of groups are often in geographical communities, but regularly online or hybrid, too, like peer-to-peer mental health support groups such as the Mentally Aware Nigeria Initiative.

What makes communities of care both scalable and game-changing for the mental health of those involved in change-making is the quality, care and commitment of relationships, making decisions together and dealing with conflict from the perspective of justice. Whether you look at the scientific studies on coping with climate-related mental health issues, the wellbeing and resilience of communities hit by heatwaves, hurricanes and floods, or international networks of climate justice activists, what appears over and over again as a foundation for collective wellbeing and resilience is a dense, mutually supportive web of relationships – just like any thriving ecosystem. Thankfully, they’re not that hard to find.

We urgently need to redefine who has power

BW: The scientific literature shows very clearly that people with pre-existing mental illness are disproportionately harmed by the mental health impacts of the climate crisis. What I love so much about your book is how you bring those findings to life by being courageous, sharing your own story of mental health issues that touch on psychosis, bipolar, suicidality, and how they interweave with climate awareness/climate activism.

If you could speak to every researcher on earth right now who is looking at the intersection of climate change and mental health in their work, what would you most want them to know about how they should be approaching the question of how people with pre-existing mental health diagnoses are impacted, on a mental/emotional/psychological level, by the climate crisis?

Thank you. As someone who kind of straddles these spaces, the biggest blindspot I’ve noticed is power dynamics. The scientific community is seeing a resurgence of lived experience, lived expertise and the importance of systemic thinking. That’s exhilarating, and long overdue, but there’s a chasm between most medical approaches and theories of personal growth in the context of social change, especially when it comes to climate change’s impacts and potential responses. I was on a call recently where academics, medical practitioners and activists all over the world shared their perspectives about climate/mental health, but it was capped at the end by one of the hosts saying that the solution was to collect more data because (I’m paraphrasing here) “if we have enough data we can’t not do the right thing.” That is clearly, demonstrably untrue. Just take the deluge of climate data we’ve had for decades and the utter disconnect between “empirical’ knowledge” and “doing the right thing”.

We need to centre those people with the most intimate experiences of climate x mental health. That has to acknowledge that a lot of people legitimately don’t feel that “mental health” is an acceptable or legitimate framing, for instance, partly because it’s a further imposition of modernity onto communities that never agreed to ascribe to that cosmology. People need agency and power to put that experience into practice, not just be consulted. That’s a systemic issue, and the medical and scientific community have a relationship to it even when they position themselves as apolitical.

Dr. Asma Humayun is a psychiatrist working on innovative collectivized models of mental health and psychosocial support in Pakistan. She talked to me about meeting people affected by last year’s biblical-scale floods with conversation and collaborative support, letting them direct the recovery process by basing it on their previous networks of care, which had largely been washed away. The WHO approach might, conversely, be to advise psychiatrists to go into a community with enough antidepressants to give the predicted 20% of the population pharmacological aid. I’m being slightly reductive, but there are countless examples of this inappropriate, ineffective and unnecessarily surface-level airdropping of bio-medical support.

Dr. Elaine Flores, who studies the psychological and social resilience of climate-affected people all over the world has repeatedly emphasized to me that a vital element in community recovery post-disaster is the density of social relationships of support. It’s the people who live there who do the work, facilitated by medical professionals as and when necessary and appropriate. The same thing happened in New Zealand when I was there last year. A massive cyclone hit and it was the communities with pre-existing mutual aid groups that thrived and helped others.

This comes back to rushing. The scientific community has made leaps and bounds in understanding and implementing more systemic models of health, whether it’s the UN’s One Health Program linking ecosystems and livestock with health, or research collaborations like Imperial College’s Climate Cares project, new trainings for therapists in Climate Aware Psychology/Psychiatry or Care of People x Planet (COP2). However, we can’t assume that one very specific branch of empiricism – of collecting and formalizing knowledge within academic and medical contexts – can fix things. This has its place, but we need to change the process and the power dynamics. Cultivating mutual-aid networks and peer-to-peer support groups is a good place to enter this work, but fundamentally we have to revolutionize who it is that decides, not ‘informs’ but decides, how knowledge and expertise (lived or academic) evolves into action in the material world. That’s unavoidably about redistributing power, and it’ll lead to a flowering of radical alternative worlds.

Post-traumatic growth: a crucial term to know

BW: What’s the biggest gift you’ve received from the mental health issues you live with for motivating or maintaining transformational climate action?

Wow. Post-traumatic growth. Hands down. Basically everyone knows what post-traumatic stress is (there are people talking about pre-traumatic stress related to climate change, too), but few are familiar with PTG. After severe trauma, it’s possible for people to restructure their lives and have their worldviews realigned through the process of recovery, giving newfound meaning, purpose and belonging. I was lucky enough to have the social supports and communities after my suicide attempt to experience a bit of that. After my fall my world (and my body) was pretty shattered. I spent a month in a coma, six months in hospital and was spat out into lockdown in a wheelchair. I think my dissociation, the PTSD-induced state of unreality I still live with, and the memory disintegration from all my ECT meant that there was a certain amount of cognitive flexibility that let me reevaluate my life pretty fresh.

Over years, I drew on the embodied patience I’ve learned from years of mental and physical disability, played with the alternate shape-shifting realities and psychotic hallucinations as intriguing pointers rather than nightmares and, fundamentally, been able to highlight the necessary elements of self-care and healing that make it possible for me to function in a system that I’ve often felt doesn’t want me to exist. I’ve also learnt a lot about radical inclusivity – from both sides – and been able to find comfort in shutting the hell up and actually listening. Ceding control, experientially, from having it taken from you by the world. That’s built more durable and reliable relationships, and taken the sting of urgency, stress and tension out of working with people who are on the same page.

I need to say: I’ve been extraordinarily lucky. I’m especially lucky in that the relationships I’ve maintained as I’ve healed have strengthened and deepened, which for a long time had very little to do with me. There are gifts in madness, but – and this is absolutely fundamental – I could only access them because I was given the support, structure and safety. Most people on the planet don’t have it. Softly and consistently offer that sanctuary to those you love, be patient, and it will only multiply.

Charlie’s new book Spinning Out is available for pre-order now. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked reading this, feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack 🙏🏼

If you are feeling suicidal, there are ways to cope and overcome the pain. The following crisis lines and resources can help you find support.

Making Waves

Expectant is a six-part audio series by Pippa Johnstone that sits on the fence between imagination and reality, between becoming a parent during the climate crisis and deciding to remain childfree. Through conversations with climate researchers, parents, mental health experts and childfree families, she grapples with grief, hope, and the biggest decision of her life: should she bring a child into this world?

Ps: Expectant Ep. 4 features her conversation with our own Britt Wray and it publishes today! So don’t miss it 😀

Read this timely article by Aryn Baker where doctors and scientists (including our own Britt Wray) unravel the complex interplay between extreme heat and mental health, to help us understand how high temperatures affect the brain and wellbeing outcomes.

As always, you can share your thoughts and reach the Gen Dread community by commenting on this article or replying to this email. You can also follow along on Twitter and Instagram.

‘Till next time!

Sorry for your loss. I hope you take time to reflect and see that COVID/climate hysteria is weaponized against mental health. The goal is to instill fear so you give more power to governments and corporations. Perhaps you can write a piece about the many thousands of African children who work in hazardous mines to extract rare earth minerals for your phones, electric cars, and solar panels.

I am sorry to see this comment section devolve into attacks on each other, which might lead to this important interview to get lost or forgotten over the back and forth of these comments.

Charlie's experience is sadly far too common, and I appreciate the open, honest and cogent reflection on climate change and mental health, including suicidality. There are so many great suggestions here on how to be with people who are in this difficult place. And also lots of great suggestions of how to prepare your community to be a safe haven for more and more people in despair and distress.

Let's not lose one single other person to this combination of pains!!!!

Thanks, Britt and Charlie for this submission!